We have recently won a major grant (around £2 million over 5 years) under the EPSRC Contrails call which we will be using to set up the “Cambridge Cloud Cybercrime Centre”:

https://www.cambridgecybercrime.uk/

The will be a multi-disciplinary initiative combining expertise from the University of Cambridge’s Computer Laboratory, Institute of Criminology and Faculty of Law. We will be operational from 1 October 2015.

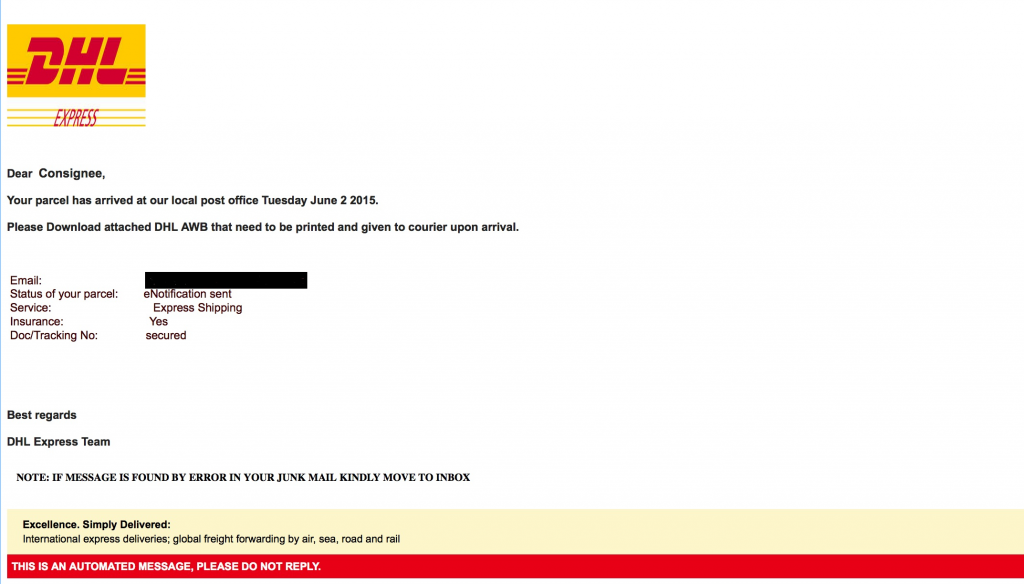

Our approach will be data driven. We have already negotiated access to some very substantial datasets relating to cybercrime and we aim to leverage our neutral academic status to obtain more data and build one of the largest and most diverse data sets that any organisation holds.

We will mine and correlate these datasets to extract information about criminal activity. Our analysis will enhance understanding of crime ‘in the cloud’, enable us to devise identifiers of such criminality, allow us to build systems to detect this type of crime when it occurs, and aid us in showing how it is possible to collect extremely reliable evidence of wrongdoing. When it is appropriate, we will work closely with law enforcement so that interventions can be undertaken.

Our overall objective is to create a sustainable and internationally competitive centre for academic research into cybercrime.

Importantly, we will not be keeping all this data to ourselves… a key aim of our Centre is to make data available to other academics for them to apply their own skills to address cybercrime issues.

Academics currently face considerable difficulties in researching cybercrime. It is difficult, and time consuming, to negotiate access to real data on actual abuse and then it is necessary to build and deploy data collection tools before the real work can even be started.

We intend to drive a step change in the amount of cybercrime research by making datasets available, not just of URLs but content as well, so that other academics can concentrate on their particular areas of expertise and start being productive immediately. These datasets will be both ‘historic’ and, where appropriate ‘real-time’.

We will maintain high ethical standards in everything we do and will develop a strong legal framework for our operations. In particular we will always ensure that the data we handle is treated fully in accord with the spirit, and not just the letter, of the agreements we enter into.

We will shortly be hiring for the first few research positions … pointers to the job adverts will appear on this blog.