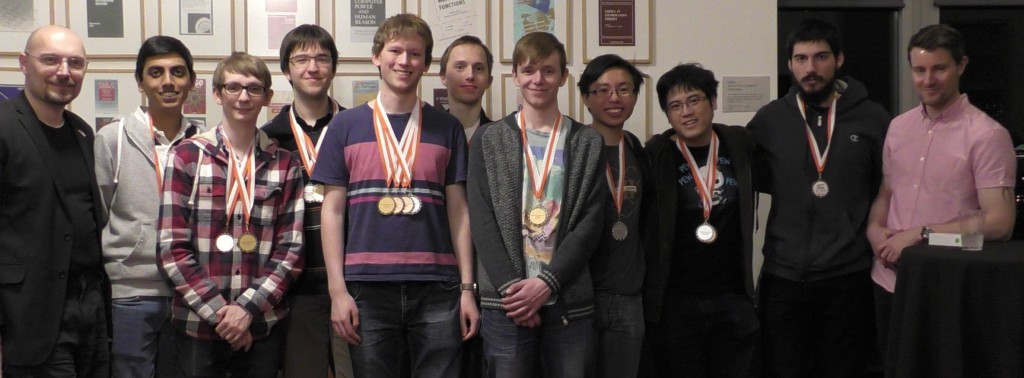

The best student hackers from the UK’s 13 Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Research are coming to Cambridge for the first Inter-ACE Cyberchallenge tomorrow, Saturday 23 April 2016.

All posts by Frank Stajano

Three exciting job openings in security usability

We are looking for three more people to join the Cambridge security group. Two job adverts, intended for postgrads or postdocs, are already out now. A third one, specifically aimed at a final year undergraduate or master student, strong on programming but with no significant work experience, is currently making its way through the HR pipeline and should appear soon. Please pass this on to anyone potentially interested.

- User experience (UX) designer

Research Associate or Assistant (with/without PhD)

Start date: ASAP

Details and link to application form: http://www.jobs.cam.ac.uk/job/9244/ - Senior software engineer / software engineer

Research Associate or Assistant (with/without PhD)

Start date: ASAP

Details and link to application form: http://www.jobs.cam.ac.uk/job/9245/ - Software engineer

Research assistant (having just completed a bachelor or master in CS/EE)

Start date: June 2016

Watch this space: the ad should go live within a week or so

https://www.mypico.org/jobs/

Passwords 2015 at Cambridge

A very exciting Passwords 2015 is being hosted at the Computer Laboratory from 7 to 9 December. A unique conference that brings together the world’s top password hackers and academics. It is being liveblogged by the participants on Twitter with the hashtag #passwords15. A live feed is available on the Passwords 2015 page.

Double bill: Password Hashing Competition + KeyboardPrivacy

Two interesting items from Per Thorsheim, founder of the PasswordsCon conference that we’re hosting here in Cambridge this December (you still have one month to submit papers, BTW).

First, the Password Hashing Competition “have selected Argon2 as a basis for the final PHC winner”, which will be “finalized by end of Q3 2015”. This is about selecting a new password hashing scheme to improve on the state of the art and make brute force password cracking harder. Hopefully we’ll have some good presentations about this topic at the conference.

Second, and unrelated: Per Thorsheim and Paul Moore have launched a privacy-protecting Chrome plugin called Keyboard Privacy to guard your anonymity against websites that look at keystroke dynamics to identify users. So, you might go through Tor, but the site recognizes you by your typing pattern and builds a typing profile that “can be used to identify you at other sites you’re using, were identifiable information is available about you”. Their plugin intercepts your keystrokes, batches them up and delivers them to the website at a constant pace, interfering with the site’s ability to build a profile that identifies you.

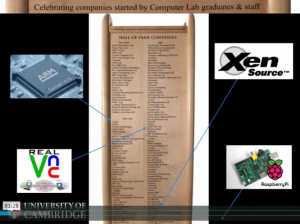

Commercialising academic research

At the 2014 annual conference of the Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber-Security Research I was invited to give a talk on commercialising research from the viewpoint of an academic. I did that by distilling the widsom and experience of five of my Cambridge colleagues who had started a company (or several). The talk was well received at the conference and may be instructive both for academics with entrepreneurial ambitions and for other universities that aspire to replicate the “Cambridge phenomenon” elsewhere.

A recording of the presentation, Commercialising research: the academic’s perspective from Frank Stajano Explains, is available on Vimeo.

Passwords’14 in Trondheim

Passwords^14 is part of a lively and entertaining conference series started by password hacker Per Thorsheim in 2010 and devoted solely to passwords.

Up to now it was mostly invited talks and hacks but this year we’re also having scientific papers, which will be peer-reviewed. Proceedings will be published in Springer LNCS. Submission deadline 27 October 2014.

Call for papers: http://passwords14.com/cfp.pdf

Conference site: https://passwordscon.org/

See you in Trondheim, Norway, 8-10 December 2014.

Pico part I: Russian hackers stole a billion passwords? True or not, with Pico you wouldn’t worry about it.

In last week’s news (August 2014) we heard that Russian hackers stole 1.2 billion passwords. Even though such claims sound somewhat exaggerated, and not correlated with a proportional amount of fraudulent access to user accounts, password compromise is always a pain for the web sites involved—more so when it causes direct reputation damage by having the company name plastered on the front page of the Financial Times, as happened to eBay on 22 May 2014 after they lost to cybercriminals the passwords of over 100 million users. Shortly before that, in April 2014, it was the Heartbleed bug that forced password resets on allegedly 66% of all websites. And last year, in November 2013, it was Adobe who lost the passwords of 150 million users. Keep going back and you’ll find many more incidents. With alarming frequency we hear of some major security exploit that compromises an enormous number of passwords and embarrasses web sites into asking their users to pick a new password.

Note the irony: despite the complaints from some arrogant security experts that users are too lazy or too dumb to pick strong passwords, when such attacks take place, all users must change their passwords, not just those with a weak one. Even the diligent users who went to the trouble of following complicated instructions and memorizing “avKpt9cpGwdp”, not to mention typing it every day, are punished, for a sin they didn’t commit (the insecurity of the web site) just as much as the allegedly lazy ones who picked “p@ssw0rd” or “1234”. This is fundamentally unfair.

My team has been working on Pico, an ambitious project to replace passwords with a fairer system that does not require remembering secrets. The primary goal of Pico is to be easier to use than remembering a bunch of PINs and passwords; but, incidentally, it’s also meant to be much more secure. On that note, because Pico uses public key cryptography, if a Pico-based web site is compromised, then its users do not need to change their login credentials. The attackers can only steal the users’ public keys, not their private keys, and therefore are not able to impersonate them, neither at that site nor anywhere else (besides the fact that, to protect your privacy, your Pico uses a different key pair for every one of your accounts). This alone, even aside from any usability improvements, should be a good enough reason for web sites to convert to Pico.

We didn’t blog it then, but a few months ago we produced a short introductory video of our vision for Pico. On the Pico web site, besides that video and others, there are also frequently asked questions and, for those wanting to probe more deeply, a growing collection of technical papers.

This is the first part in a series on the Pico project: my research associates will follow it up with further developments. Pico was recently featured in The Observer and on Sophos’s Naked Security blog, and is about to feature on BBC Radio 4’s PM programme on Tuesday 19 August at 17:00 (broadcast on Thursday 21 August 2014, with a slight cut; currently on iPlayer, starting at 46:28 . Full version broadcast on BBC World Service and downloadable, for a while, from the BBC Global News Podcast, starting at 21:37 ).

Update: the Pico web site now has a page with press coverage.

Job opening: post-doctoral researcher in usable security

(post UPDATED with new job opening)

I am delighted to announce a job opening in the Cambridge Security Group. Thanks to generous funding from the European Research Council I am in a position to recruit several post-doc research associates to work with me on the Pico project, whose ambitious aim is ultimately to liberate the world from the annoyance and insecurity of passwords, which everyone hates.

In previous posts I hinted at why it’s going to be quite difficult (Oakland paper) and what my vision for Pico is (SPW paper, USENIX invited talk). What I want to do, now that I have the investment to back my idea, is to assemble an interdisciplinary team of the best possible people, with backgrounds not just in security and software but crucially in psychology, interaction design and embedded hardware. We’ll design and build a prototype, build a batch of them and then have real people (not geeks) try them out and tell us why they’re all wrong. And then design and build a better one and try it out again. And iterate as necessary, always driven by what works for real humans, not technologists. I expect that the final Pico will be rather different, and a lot better, than the one I envisaged in 2011. Oh, and by the way, to encourage universal uptake, I already promised I won’t patent any of it.

As I wrote in the papers above, I don’t expect we’ll see the end of passwords anytime soon, nor that Pico will displace passwords as soon as it exists. But I do want to be ready with a fully worked out solution for when we finally collectively decide that we’ve had enough.

Imagine we could restart from zero and do things right. Have you got a relevant PhD or are about to get one? Are you keen to use it to change the world for the better? Are you best of the best, and have the track record to prove it? Are you willing to the first member of my brilliant interdisciplinary team? Are you ready for the intellectually challenging and stimulating environment of one of the top research universities in the world? Are you ready to be given your own real challenges and responsibilities, and the authority to be in charge of your work? Then great, I want to hear from you and here’s what you need to do to apply (post UPDATED with new opening).

(By the way: I’m off to Norway next week for passwords^12, a lively 3-day conference organized by Per Thorsheim and totally devoted to nothing else than passwords.)

The quest to replace passwords

As any computer user already knows, passwords are a usability disaster: you are basically told to “pick something you can’t remember, then don’t write it down“, which is worse than impossible if you must also use a different password for every account. Moreover, security-wise, passwords can be shoulder-surfed, keylogged, eavesdropped, brute-forced and phished. Notable industry insiders have long predicted their demise. Over the past couple of decades, dozens of alternative schemes have been proposed. Yet here we are in 2012, still using more and more password-protected accounts every year. Why? Can’t we do any better? Don’t the suggested replacements offer any improvements?

The paper I am about to present at the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy in San Francisco (Oakland 2012), grown out of the “related work” section of my earlier Pico paper and written with coauthors Joe Bonneau, Cormac Herley and Paul van Oorschot, offers a structured and well-researched answer that, according to peer review, “should have considerable influence on the research community”. It offers, as its subtitle says, a framework for comparative evaluation of password replacement schemes.

We build a large 2D matrix. Across the columns we define a broad spectrum of 25 benefits that a password replacement scheme might potentially offer, starting with USABILITY benefits, such as being easy to learn, or not requiring a memory effort from the user, and SECURITY benefits, such as resilience to shoulder-surfing or to phishing. These two broad categories, and the tension between them, are relatively well-understood: it’s easy to provide more usability by offering less security and vice versa. But we also introduce a third category, DEPLOYABILITY, that measures how easy it would be to deploy the scheme on a global scale, taking into account such benefits as cost per user, compatibility with deployed web infrastructure and accessibility to people with disabilities.

Next, in the rows, we identify 35 representative schemes covering 11 broad categories, from password managers through federated authentication to hardware tokens and biometric schemes. We then carefully rate each scheme individually, with various cross-checks to preserve accuracy and consistency, assessing for each benefit whether the given scheme offers, almost offers or does not offer the benefit. The resulting colourful matrix allows readers to compare features at a glance and to recognize general patterns that would otherwise be easily missed.

Contrary to the optimistic claims of scheme authors, who often completely ignore some evaluation criteria when they assert that their scheme is a definite improvement, none of the examined schemes does better than passwords on every benefit when rated on all 25 benefits of this objective benchmark.

From the concise overview offered by the summary matrix we distil key high level insights, such as why we are still using passwords in 2012 and are probably likely to continue to do so for quite a while.

How can we make progress? It has been observed that many people repeat the mistakes of history because they didn’t understand the history book. In the field of password replacements, it looks like a good history book still needed to be written! As pointed out during peer review, our work will be a foundational starting point for further research in the area and a useful sanity check for future password replacement proposals.

An extended version of the paper is available as a tech report.

Pico: no more passwords (at Usenix Security)

The usability community has long complained about the problems of passwords (remember the Adams and Sasse classic). These days, even our beloved XKCD has something to say about the difficulties of coming up with a password that is easy to memorize and hard to brute-force. The sensible strategy suggested in the comic, of using a passphrase made of several common words, is also the main principle behind Jakobsson and Akavipat’s fastwords. It’s a great suggestion. However, in the long term, no solution that requires users to remember secrets is going to scale to hundreds of different accounts, if all those remembered secrets have to be different (and changed every couple of months).

This is why, as I previously blogged, I am exploring the space of solutions that do not require the memorization of any secrets—whether passwords, passphrases, PINs, faces, graphical squiggles or anything else. My SPW paper, Pico: No more passwords, was finalized in June (including improvements suggested in the comments to the previous blog post) and I am about to give an invited talk on Pico at Usenix Security 2011 in San Francisco.

Usenix talks are recorded and the video is posted next to the abstracts: if you are so inclined, you will be able to watch my presentation shortly after I give it.

To encourage adoption, I chose not to patent any aspect of Pico. If you wish to collaborate, or fund this effort, talk to me. If you wish to build or sell it on your own, be my guest. No royalties due—just cite the paper.