The best student hackers from the UK’s 13 Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Research are coming to Cambridge for the first Inter-ACE Cyberchallenge tomorrow, Saturday 23 April 2016.

The event is organized by the University of Cambridge in partnership with

Facebook. It is loosely patterned on other inter-university sport competitions, in that each university enters a team of four students and the winning team takes home a trophy that gets engraved with the name of their university and is then passed on to the next winning team the following year.

Participation in the Inter-ACE cyberchallenge is open only to Universities accredited as ACEs under the EPSRC/GCHQ scheme. 10 of the 13 ACEs have entered this inaugural edition: alphabetically, Imperial College, Queens University Belfast, Royal Holloway University of London, University College London, University of Birmingham, University of Cambridge (hosting), University of Kent, University of Oxford, University of Southampton, University of Surrey. The challenges are set and administered by Facebook, but five of the ten competing insitutions have also sent Facebook an optional “guest challenge” for others to solve.

The players compete in a CTF involving both “Jeopardy-style” and “attack-defense-style” aspects. Game progress is visualized on a world map somewhat reminiscent of Risk, where teams attempt to conquer and re-conquer world countries by solving associated challenges.

We designed the Inter-ACE cyberchallenge riding on the success of the

Cambridge2Cambridge cybersecurity challenge we ran in collaboration with MIT last March. In that event, originally planned following a January 2015

joint announcement by US President Barack Obama and UK Prime Minister David Cameron, six teams of students took part in a 24-hour Capture-The-Flag involving several rounds and spin-out individual events such as “rapid fire” (where challengers had to break into four different vulnerable binaries under time pressure) and “lock picking”, also against the clock and against each other. The challenges were expertly set and administered by

ForAllSecure, a cybersecurity spin-off from Carnegie Mellon University.

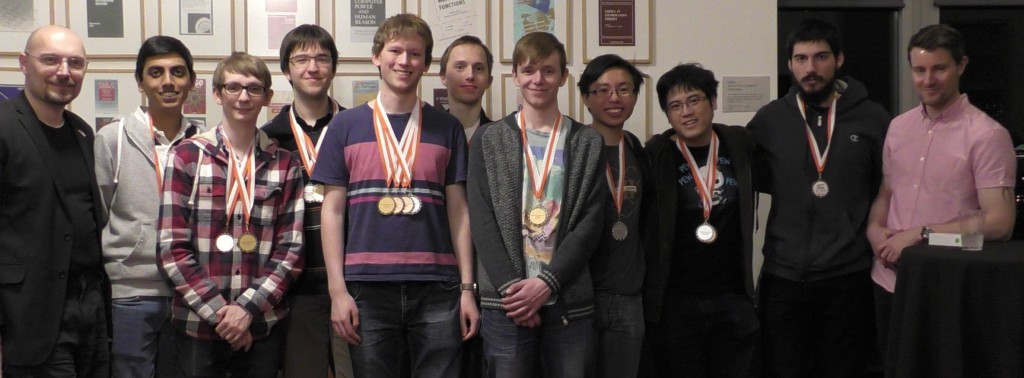

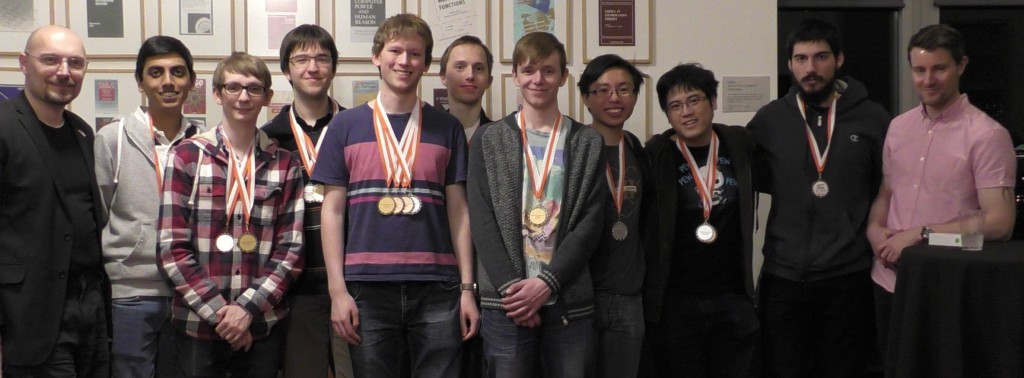

With generous support from the UK consulate in Boston we were able to fly 10 Cambridge students to MIT. By design, we mixed people from both universities in each team, to promote C2C as an international cooperation and a bridge-building exercise. Thanks to the generosity of the many sponsors of the event, particularly Microsoft who funded the cash prizes, the

winning team “Johnny Cached”, consisting of two MIT and two Cambridge students, walked away with 15,000 USD. Many other medals were awarded for various achievements throughout the event. Everyone came back with a sense of accomplishement and with connections with new like-minded and highly skilled friends across the pond.

In both the C2C and the Inter-ACE I strived to design the rules in a way that would encourage participation not just from the already-experienced but also from interested inexperienced students who wanted to learn more. So, in C2C I designed a scheme where (following a pre-selection to rank the candidates) each team would necessarily include both experienced players and novices; whereas in Inter-ACE, where each University clearly had the incentive of picking their best players to send to Cambridge to represent them, I asked our technical partners Facebook to provide a parallel online competition that could be entered into remotely by individual students who were not on their ACE’s team. This way nobody who wanted to play is left out.

As an educator, I believe the role of a university is to

teach the solid foundations, the timeless principles, and especially “

learning how to learn”, rather than the trick of the day; so I would not think highly of a hacking-oriented university course that primarily taught techniques destined to become obsolete in a couple of years. On the other hand, a total disconnect between theory and practice is also inappropriate. I’ve always introduced my students to lockpicking at the end of my undergraduate security course, both as a metaphor for the attack-defense interplay that is at the core of security (a person unskilled at picking locks has no hope of building a new lock that can withstand determined attacks; you can only beat the bad guys if you’re better than them) and to underline that the practical aspects of security are also relevant, and even fun. It has always been enthusiastically received, and has contributed to make more students interested in security.

I originally accepted to get involved in organizing Cambridge 2 Cambridge, with my esteemed MIT colleague

Dr Howie Shrobe, precisely because I believe in the educational value of exposing our students to practical hands-on security. The C2C competition was run as a purely vocational event for our students, something they did during evenings and weekends if they were interested, and on condition it would not interfere with their coursework. However, taking on the role of co-organizing C2C allowed me, with thanks to the UK Cabinet Office, to recruit a precious full time collaborator, experienced ethical hacker Graham Rymer, who has since been developing a wealth of up-to-date training material for C2C. My long term plan, already blessed by the department, is to migrate some of this material into practical exercises for our official undergraduate curriculum, starting from next year. I think it will be extremely beneficial for students to get out of University with a greater understanding of the kind of adversaries they’re up against when they become security professionals and are tasked to defend the infrastructure of the organization that employs them.

Another side benefit of these competitions, as already remarked, is the community building, the forging of links between students. We don’t want merely to train individuals: we want to create a new generation of security professionals, a strong community of “good guys”. And if they met each other at the Inter-ACE when they were little, they’re going to have a much stronger chance of actively collaborating ten years later when they’re grown-ups and have become security consultants, CISOs or heads of homeland security back wherever they came from. Sometimes I have to fight with narrow-minded regulations that would only, say, offer scholarships in security to students who could pass security clearance. Well, playing by such rules makes the pool too small. For as long as I have been at Cambridge, the majority of the graduates and faculty in our security research group have been “foreigners” (myself included, of course). A university that only worked with students (and staff, for that matter) from its own country would be at a severe disadvantage compared to those, like Cambridge, that accept and train the best in the whole world. I believe we can only nurture and bring out the best student hackers in the UK in a stimulating environment where their peers are the best student hackers from anywhere else in the world. We need to take the long term view and understand that we cannot reach critical mass without this openness. We must show how exciting cybersecurity is to those clever students who don’t know it yet, whatever their gender, prior education, social class, background, even (heaven forbid) those scary foreigners, hoo hoo, because it’s only by building a sufficiently large ecosystem of skilled, competent and ethically trained good guys that employers will have enough good applicants “of their preferred profile” in the pool they want to fish in for recruitment purposes.

My warmest thanks to my academic colleagues leading the other ACE-CSRs who have responded so enthusiastically to this call at very short notice, and to the students who have been so keen to come to Cambridge for this Inter-ACE despite it being so close to their exam season. Let’s celebrate this diversity of backgrounds tomorrow and forge links between the best of the good guys, wherever they’re from. Going forward, let’s attract more and more brilliant young students to cybersecurity, to join us in the fight to make the digital society safe for all, within and across borders.

The competition was played out on a “Risk-style” world map, and competing teams had to fight each other for control of several countries, each protected by a fiendish puzzle. A number of universities had also submitted guest challenges, and it was great that so many teams got involved in this creative process too. To give one example; The Cambridge team had designed a challenge based around a historically accurate enigma machine, with this challenge protecting the country of Panama. Competitors had to brute-force the settings of the enigma machine to decode a secret message. Other challenges were based around the core CTF subject areas of web application security, binary reverse engineering and exploitation, forensics, and crypto. Some novice teams may have struggled to compete, but they would have learned a lot, and hopefully developed an appetite for more competition. There were also plenty of teams present with advanced tool sets and a solid plan, with these preparations clearly paying off in the final scores.

The competition was played out on a “Risk-style” world map, and competing teams had to fight each other for control of several countries, each protected by a fiendish puzzle. A number of universities had also submitted guest challenges, and it was great that so many teams got involved in this creative process too. To give one example; The Cambridge team had designed a challenge based around a historically accurate enigma machine, with this challenge protecting the country of Panama. Competitors had to brute-force the settings of the enigma machine to decode a secret message. Other challenges were based around the core CTF subject areas of web application security, binary reverse engineering and exploitation, forensics, and crypto. Some novice teams may have struggled to compete, but they would have learned a lot, and hopefully developed an appetite for more competition. There were also plenty of teams present with advanced tool sets and a solid plan, with these preparations clearly paying off in the final scores.