I’m liveblogging the Workshop on Security and Human Behaviour which is being held at USC in Los Angeles. The participants’ papers are here; for background, see the liveblogs for SHB 2008-12 which are linked here and here. Blog posts summarising the talks at the workshop sessions will appear as followups below. (Added: there is another liveblog by Vaibhav Garg.)

Category Archives: Social networks

Current issues in payments (part 1)

In this first of a two or three part instalment. In them Laurent Simon and I comment on our impressions of David Birch’s Tomorrow’s Transactions Forum, which we attended thanks to Dave’s generosity.

NOTE: Although written in first person, what follows results from a combination of Laurent’s and my notes.

This was a two day event for a handful of guests to foster communication and networking. I appreciated the format.

After a brief introduction, the first day kicked off with my ever growing presentation on the origins of the cashless society (you can see it here ).

The following act was Tillman Bruett (UNCDF), who was involved in the drafting of The journey towards cash-lite (at least so say the acknowledgements).

Continue reading Current issues in payments (part 1)

Security and Human Behaviour 2012

Cloudy with a Chance of Privacy

Three Paper Thursday is an experimental new feature in which we highlight research that group members find interesting.

When new technologies become popular, we privacy people are sometimes miffed that nobody asked for our opinions during the design phase. Sometimes this leads us to make sweeping generalisations such as “only use the Cloud for things you don’t care about protecting” or “Facebook is only for people who don’t care about privacy.” We have long accused others of assuming that the real world is incompatible with privacy, but are we guilty of assuming the converse?

On this Three Paper Thursday, I’d like to highlight three short papers that challenge these zero-sum assumptions. Each is eight pages long and none requires a degree in mathematics to understand; I hope you enjoy them.

Metrics for dynamic networks

There’s a huge literature on the properties of static or slowly-changing social networks, such as the pattern of friends on Facebook, but almost nothing on networks that change rapidly. But many networks of real interest are highly dynamic. Think of the patterns of human contact that can spread infectious disease; you might be breathed on by a hundred people a day in meetings, on public transport and even in the street. Yet if we were facing a flu pandemic, how could we measure whether the greatest spreading risk came from high-order static nodes, or from dynamic ones? Should we close the schools, or the Tube?

Today we unveiled a paper which proposes new metrics for centrality in dynamic networks. We wondered how we might measure networks where mobility is of the essence, such as the spread of plague in a medieval society where most people stay in their villages and infection is carried between them by a small number of merchants. We found we can model the effects of mobility on interaction by embedding a dynamic network in a larger time-ordered graph to which we can apply standard graph theory tools. This leads to dynamic definitions of centrality that extend the static definitions in a natural way and yet give us a much better handle on things than aggregate statistics can. I spoke about this work today at a local workshop on social networking, and the paper’s been accepted for Physical Review E. It’s joint work with Hyoungshick Kim.

Security and Human Behaviour 2011

Can we Fix Federated Authentication?

My paper Can We Fix the Security Economics of Federated Authentication? asks how we can deal with a world in which your mobile phone contains your credit cards, your driving license and even your car key. What happens when it gets stolen or infected?

Using one service to authenticate the users of another is an old dream but a terrible tar-pit. Recently it has become a game of pass-the-parcel: your newspaper authenticates you via your social networking site, which wants you to recover lost passwords by email, while your email provider wants to use your mobile phone and your phone company depends on your email account. The certification authorities on which online trust relies are open to coercion by governments – which would like us to use ID cards but are hopeless at making systems work. No-one even wants to answer the phone to help out a customer in distress. But as we move to a world of mobile wallets, in which your phone contains your credit cards and even your driving license, we’ll need a sound foundation that’s resilient to fraud and error, and usable by everyone. Where might this foundation be? I argue that there could be a quite surprising answer.

The paper describes some work I did on sabbatical at Google and will appear next week at the Security Protocols Workshop.

Social network security – an oxymoron?

The New York Times has followed up the recent Twitter hack with an online debate on social network security for which I wrote a short piece.

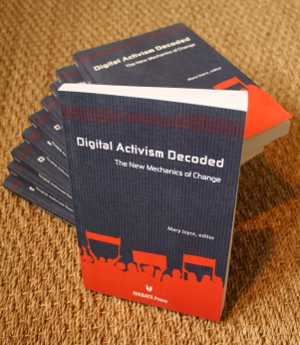

Digital Activism Decoded: The New Mechanics of Change

The book “Digital Activism Decoded: The New Mechanics of Change” is one of the first on the topic of digital activism. It discusses how digital technologies as diverse as the Internet, USB thumb-drives, and mobile phones, are changing the nature of contemporary activism.

Each of the chapters offers a different perspective on the field. For example, Brannon Cullum investigates the use of mobile phones (e.g. SMS, voice and photo messaging) in activism, a technology often overlooked but increasingly important in countries with low ratios of personal computer ownership and poor Internet connectivity. Dave Karpf considers how to measure the success of digital activism campaigns, given the huge variety of (potentially misleading) metrics available such as page impression and number of followers on Twitter. The editor, Mary Joyce, then ties each of these threads together, identifying the common factors between the disparate techniques for digital activism, and discussing future directions.

My chapter “Destructive Activism: The Double-Edged Sword of Digital Tactics” shows how the positive activism techniques promoted throughout the rest of the book can also be used for harm. Just as digital tools can facilitate communication and create information, they can also be used to block and destroy. I give some examples where these events have occurred, and how the technology to carry out these actions came to be created and deployed. Of course, activism is by its very nature controversial, and so is where to draw the line between positive and negative actions. So my chapter concludes with a discussion of the ethical frameworks used when considering the merits of activism tactics.

Digital Activism Decoded, published by iDebate Press, is now available for download, and can be pre-ordered from Amazon UK or Amazon US

(available

June 30th now).

Update (2010-06-17): Amazon now have the book in stock at both their UK and US stores.

What's the Buzz about? Studying user reactions

Google Buzz has been rolled out to 150M Gmail users around the world. In their own words, it’s a service to start conversations and share things with friends. Cynics have said it’s a megalomaniacal attempt to leverage the existing user base to compete with Facebook/Twitter as a social hub. Privacy advocates have rallied sharply around a particular flaw: the path of least-resistance to signing up for Buzz includes automatically following people based on Buzz’s recommendations from email and chat frequency, and this “follower” list is completely public unless you find the well-hidden privacy setting. As a business decision, this makes sense, the only chance for Buzz to make it is if users can get started very quickly. But this is a privacy misstep that a mandatory internal review would have certainly objected to. Email is still a private, personal medium. People email their mistresses, workers email about job opportunities, reporters email anonymous sources all with the same emails they use for everything else. Besides the few embarrassing incidents this will surely cause, it’s fundamentally playing with people’s perceptions of public and private online spaces and actively changing social norms, as my colleague Arvind Narayanan spelled out nicely.

Perhaps more interesting than the pundit’s responses though is the ability to view thousands of user’s reactions to Buzz as they happen. Google’s design philosophy of “give minimal instructions and just let users type things into text boxes and see what happens” preserved a virtual Pompeii of confused users trying to figure out what the new thing was and accidentally broadcasting their thoughts to the entire Internet. If you search Buzz for words like “stupid,” “sucks,” and “hate” the majority of the conversation so far is about Buzz itself. Thoughts are all over the board: confusion, stress, excitement, malaise, anger, pleading. Thousands of users are badly confused by Google’s “follow” and “profile” metaphors. Others are wondering how this service compares to the competition. Many just want the whole thing to go away (leading a few how-to guides) or are blasting Google or blasting others for complaining.

It’s a major data mining and natural language processing challenge to analyze the entire body of reactions to the new service, but the general reaction is widespread disorientation and confusion. In the emerging field of security psychology, the first 48 hours of Buzz posts could provide be a wealth of data about about how people react when their privacy expectations are suddenly shifted by the machinations of Silicon Valley.