By Maria Bada & Ildiko Pete

Internet of Things (IoT) solutions, which have permeated our everyday life, present a wide attack surface. They are present in our homes in the form of smart home solutions, and in industrial use cases where they provide automation. The potentially profound effects of IoT attacks have attracted much research attention. We decided to analyse the IoT landscape from a novel perspective, that of the hacking community.

Our recent paper published at the 7th IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS 2020) presents an analysis of underground forum discussions around Shodan, one of the most popular search engines of Internet facing devices and services. In particular, we explored the role Shodan plays in the cybercriminal ecosystem of IoT hacking and exploitation, the main motivations of using Shodan, and popular targets of exploits in scenarios where Shodan is used.

To answer these questions, we followed a qualitative approach and performed a thematic analysis of threads and posts extracted from 19 underground forums presenting discussions from 2009 to 2020. The data were extracted from the CrimeBB dataset, collected and made available to researchers through a legal agreement by the Cambridge Cybercrime Centre (CCC). Specifically, the majority of posts we analysed stem from Hackforums (HF), one of the largest general purpose hacking forums covering a wide range of topics, including IoT. HF is also notable for being the platform where the source code of the Mirai malware was released in 2016 (Chen and Y. Luo, 2017).

The analysis revealed that Shodan provides easier access to targets and simplifies IoT hacking. This is demonstrated for example by discussions that centre around selling and buying Shodan exports, search results that can be readily used to target vulnerable devices and services. Forum members also expressed this view directly:

‘… Shodan and other tools, such as exploit-db make hacking almost like a recipe that you can follow.’

From the perspective of hackers a significant factor determining the utility of Shodan is if those targets can indeed be utilised. For example, whether all scanned hosts in scan results are active and whether they can be used for exploitation. Thus, the value of Shodan as a hacking tool is determined by its intended use cases.

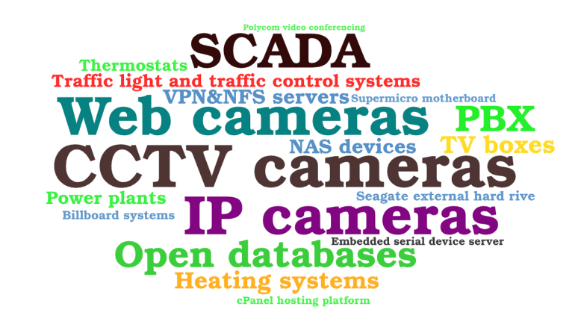

The discussions were ripe with tutorials on various aspects of hacking, which provided a glimpse into the methodology of hacking in general, hacking IoT devices, and the role Shodan plays in IoT attacks. The discussions show that Shodan and similar tools, such as Censys and Zoomeye, play a key role in passive information gathering and reconnaissance. The majority of users agree that Shodan provides value and is a useful tool and do suggest its use. They mention Shodan both in the context of searching for targets and exploiting devices or services with known vulnerabilities. As to the targets of information gathering and exploitation, we found multiple devices and services, including web cameras, industrial control systems, open databases, to mention a few.

Shodan is a versatile tool and plays a prominent role in various use cases. Since IoT devices can potentially expose personally identifiable information, such as health records, user names and passwords, members of underground forums actively discuss utilising Shodan for gathering such data. In particular, this can be achieved by exploiting open databases.

Members of forums discuss accessing remote devices for various reasons. In some cases, it is for fun, while more maliciously inclined actors can use such exploits to collect images and videos and use them in for example extortion use cases. Previous research has shown that camera systems represent easy targets for hackers. Accordingly, our findings highlight that these systems are one of the most popular targets, and they are widely discussed in the context of watching the video stream or listening to the audio stream of a compromised vulnerable cameras, or exposing someone through their camera recording. Users frequently discuss IP camera trolling, and we found posts sharing leaked video footage and websites that list hacked cameras.

Shodan, and in particular the Shodan API can be used to automate scanning for devices which could be used to create a botnet:

‘…you don’t need fancy exploits to get bots just look for bad configurations on shodan.’

And finally, a major use case member discusses utilising Shodan in Distributed Reflection Denial of Service attacks, and specifically in the first step where Shodan can be used to gather a list of reflectors, for example, NTP servers.

Discussions around selling or buying Shodan accounts show that forum members trade these accounts and associated assets due to Shodan’s credit model, which limits its use. To effectively utilise the output of Shodan queries, premium accounts are required as they provide the necessary scan, query and export credits.

Although Shodan and other search engines alike attract malicious actors, they are widely used by security professionals and for penetration testing to unveil IoT security issues. Raising awareness of vulnerabilities provides invaluable help in alleviating these issues. Shodan provides a variety of services, including Malware Hunter, which is a specialised Shodan crawler aimed at discovering malware command-and-control (CC) servers. The service is of great value to security professionals and in the fight against malware reducing its impact and ability to compromise targeted victims. This study contributes to IoT security research by highlighting the need for action towards securing the IoT ecosystem based on forum members’ discussions on underground forums. The findings suggest that more focus needs to be placed upon the security considerations while developing IoT devices, as a measure to prevent their malicious use.

Reference

F. Chen and Y. Luo, Industrial IoT Technologies and Applications: Second EAI International Conference, Industrial IoT 2017, Wuhu, China, March 25–26, 2017, Proceedings, ser. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering. Springer International Publishing, 2017.