Does the road wind up-hill all the way? Yes, to the very end. Will the day's journey take the whole long day? From morn to night, my friend. Christina Rossetti, 1861: Up-Hill.

This week’s COVID briefing paper takes a personal perspective as I recount my many adventures in complying with a call for testing from my local council.

So as to immerse the reader in the experience, this post is long. If you don’t have time for that, you can go directly to the briefing.

The council calls for everyone in my street to be tested

On Thursday 13 August my household received a hand-delivered letter from the chief executive of my local council. There had been an increase in cases in my area, and as a result, they were asking everyone on my street to get tested.

Dramatis personae:

- ME, a knowledge worker who has structured her life so as to minimize interaction with the outside world until the number of daily cases drops a lot lower than it is now;

- OTHER HOUSEHOLD MEMBERS, including people with health conditions, who would be shielding if shielding hadn’t ended on August 1.

Fortunately, everyone else in my household is also in a position to enjoy the mixed blessing of a lifestyle without social interaction. So, none of us reacted to the news of an outbreak amongst our neighbours with fear for our own health, considering our habits over the last six months. Rather, we were, and are, reassured that the local government was taking a lead.

My neighbour, however, was having a different experience. Like most people on our street, he does not have the same privileges I do: he works in a supermarket, he does not have a car, and his only Internet access is through his dumbphone. Days before, he had texted me at the end of his tether, because customers were not wearing masks or observing social distancing. He felt (because he is) unprotected, and said it was only a matter of time before he becomes infected. Receiving the council’s letter only reinforced his alarm.

Booking the tests

I went to the website and I booked tests for everyone in the household. It was a bit time-consuming because I had to put in all our ethnic backgrounds and our NHS numbers and NI numbers and inside leg measurements; but the process ran smooth. At that stage.

The signup process asks if you have access to a car. I do, but the passenger window doesn’t work, so I could drive myself to a testing centre but not take anyone with me. So I ordered home test kits all round.

The tests arrived the next evening, Friday 14 August; but you have to post them in a priority postbox the same day, more than an hour before last collection; I followed the instructions to wait until the next Monday.

Attempting the tests

On Monday 17 August, at 11:00, I started the testing of everyone in the household. Someone else had had a swab in hospital, and this was the same type of test (antigen), so they knew the ropes. I figured it might take an hour and a half to complete every test and put them in the post.

I went through the detailed process to register the tests. You must scan two barcodes, enter the postcode of the postbox you will use to send it, enter the time you will carry out the test, enter the time you will post it, complete two captchas to spot fire hydrants and bikes.

After the confirmation email arrived, everyone diligently watched the video that explains that EVERY DETAIL of the test must be performed PRECISELY or the test is null and void. I was the first to be tested. The experienced patient brandished the swab and homed in on my tonsils, but accidentally touched my lip en route. I threw away my test kit.

In return, I did the test on the experienced patient, who complained that I favoured the soft palate at the expense of the tonsils. I boxed the test up for posting, but feared I had botched that one too.

I went online and repeated the process to order two more home tests: NHS numbers, NI numbers, employers, ethnic background, captchas with hills and crosswalks, the works. On completion, the website informed me I’d already had tests and it was too soon to order any more. I dialled 119.

Important COVID self-testing tip

The 119 operator told me that touching the lip invalidates the kit, but touching the roof of the mouth (but not any other part of the mouth) is OK, so I could still post the ambiguous kit. So, do benefit from my experience.

Trying again

But what about my test? And I still had to post everyone else’s tests so there wasn’t time left in the day (it was now 13:30). The operator said they could book me in at a testing centre, but only on the same day. She made an appointment for 15:00, texted me the address and postcode, told me to bring hand gel and photo ID.

I packed my passport. I also (in a pandemic-relevant subplot), packed an item of medical equipment which the shielded person needs now that telemedicine is de rigueur, but which proved unusable. This was my chance to return it while I was at the post office. I masked up, entered the test centre’s postcode into Google Maps, and off I drove. It was now 14:30 and I had spent 3.5 hours on testing so far that day.

Google Maps told me I’d reached my destination, and there were several car parks there, but no testing centre. I pulled up and parked and called 119 again. It was fiercely hot that day, and fiercely hot in the car. It was 15:10 and I had missed my appointment time. The 119 operator told me the testing centre must have moved, and that I should go to another testing centre 15 miles from there. She said they were open until 19:30 and they would honour my ticket because I was sent somewhere that had moved.

Postcode problems

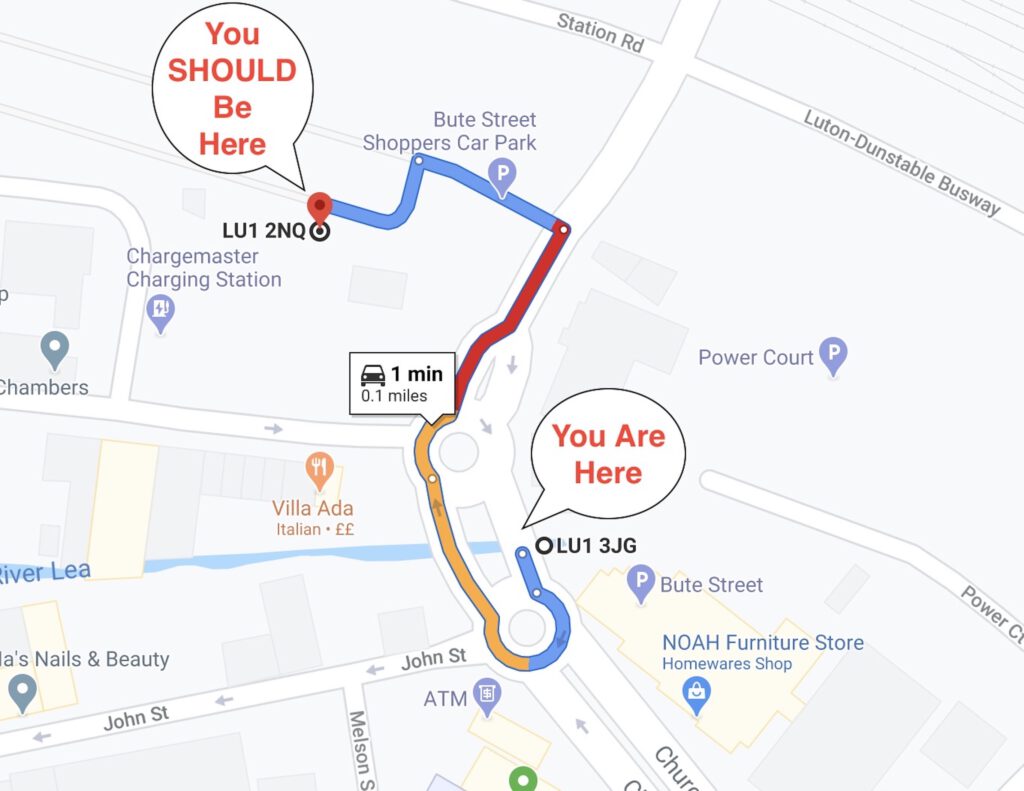

As I drove on, I saw that this car park was not on the same street as the one in the address they gave me; that street was over the intersection, continuous with the one I was on, and I was at the postcode they gave me (LU1 3JG) but I later ascertained that the right car park’s postcode ended in three different characters (LU1 2NQ).

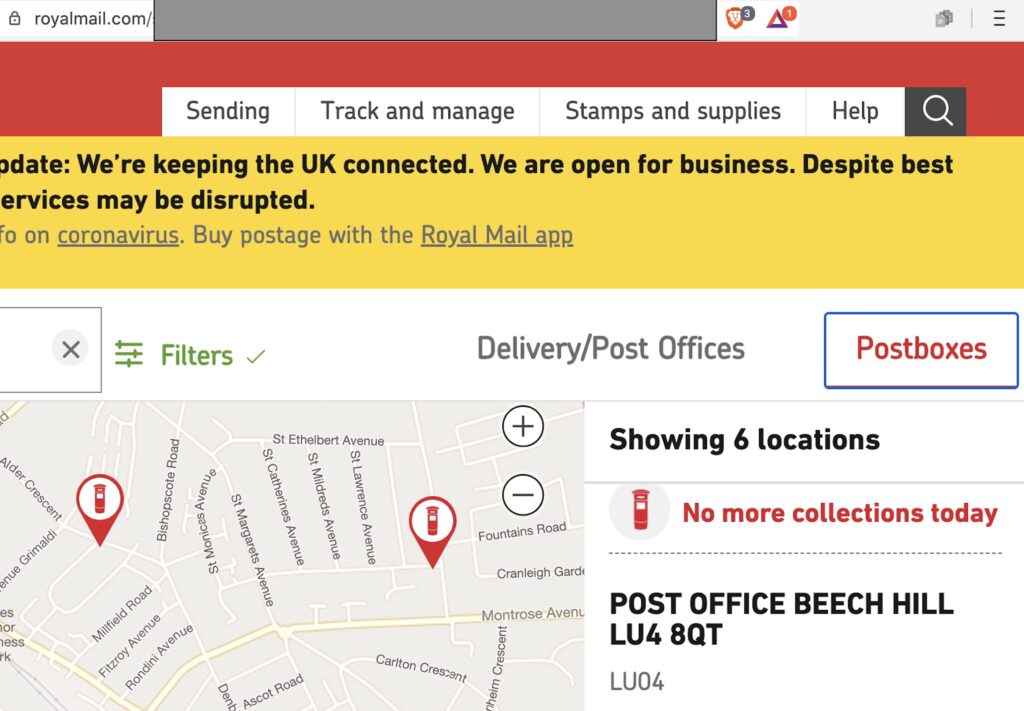

So, the right car park could have had a testing centre for all I know. But it was not until later that I checked the postcode. Because I needed to post the other tests, and you must use a priority postbox, and I was driving and you couldn’t park at the one I had planned to use.

So I entered the postcode of one of the other priority postboxes on the list in the email I received after I registered the tests, the same email that included the instruction video. This postcode was three miles away. When I got there, I was not totally surprised to find no post office and no postbox in sight.

I opened the email and clicked the links for each of the priority postboxes. The links led to the Royal Mail site, and every one came up “not found”. I searched Google Maps for the post office by name and hoped it had a priority postbox. It was 1.2 miles away, a five-minute drive. Yes, it had a designated postbox clearly marked as such. It also has a postcode (LU4 8BT) one character different from the one they gave me (LU4 8QT).

(To be fair, this one seems to be Royal Mail’s mistake)

I later worked out that although the links didn’t work, the addresses and postcodes were correct, except for the one I had driven to. Since the wrong postcode also appears on the Royal Mail website if you search a certain way, the error must have originated there, and I fell victim to it by coincidence. Whatever, I posted the other tests, mission 1 of 3 accomplished.

And now a biosecurity subplot: Post Office

Now I had to return the medical device. I went inside the post office, which was clearly signed up with “wear a mask inside this shop” signs. There were six people in the queue, at least two of whom were not wearing masks. I decided to wait outside.

I knew that by waiting outside, somebody else was going to go in and take my place in the queue. Right on time, a guy with no mask sprang into existence, asked me if there was a queue inside. I said yes, and that I’d decided to wait outside because of the mask noncompliance. Of course, he went in.

Some time later, the (maskless) last person who was ahead of me, came out. This would have been my turn. I waited.

At this point, you may have noticed that this is a very long story.

Eventually, the unmasked man came out. He helpfully told me, “There’s no-one in there.” I went in, and of course I couldn’t do a contactless payment for my postage because this was a new card after someone made a bogus charge on my old one, and you have to do one chip-and-pin to validate it first. So I had to clean down my hands and my card, but I finally got out of the post office and I set out on my journey to the testing centre.

Trying yet again

I navigated by street address this time. Won’t get fooled again. I drove up and I knew it was the right place because a woman with a green bib was talking to someone in a stationary car. Hurray!

Wait, no, that green bib was actually just a scarf. Why would someone be wearing a scarf, even a very light one, on such a fiercely hot day? I adjusted my mask, carefully, without touching the fabric. I looked again. No, there was nobody else there. Just a woman with a green scarf talking to someone in a stationary car. Eventually she realized I was there and stepped out of my way. I drove in.

I drove around and around and there were a lot of car parks around there, but no sign of any testing activity. I checked and double-checked the address, noodled around on Google Maps. I decided to leave that car park to drive around and look. The woman was still talking to someone in the stationary car. Eventually she realized I was there, let me pass, and I left the car park only to be sucked into a traffic system. After a little while I found somewhere to pull up and park. I called 119 again. I had proof that the postcodes had been wrong, but I thought they wouldn’t believe me.

But they did believe me, immediately, which on reflection is not quite as good a sign as it felt like in the moment. The operator said “they must have moved on”. I told him about the series of wrong postcodes and he said, in a voice suffused with the confidence of a self-aware but powerless node in a corporate matrix, that he would pass on the correction. My good cheer, however, was waning.

I explained that my whole street was supposed to get tested, and I had made four good-faith attempts to get tested today, and now I was done. To his credit, he pushed. He said to give him a different email address and I could get a kit by post. By now, I flat-out said I didn’t believe him, but he insisted. I gave him the new email address, gave him the verification code he sent, and was gently surprised to receive a confirmation email within seconds. So that was my home kit on the way.

It arrived on Tuesday 18 August and returned a negative result on Friday 21st – for me. At 16:42 on Wednesday 26 August, my sockpuppet – whose name is a slight variation on mine, I notice – also received a negative result, even though only one of us was tested. Each patient’s test kit is registered by barcode, so it’s plausible that I could have made a mistake by registering one test kit to myself but using a different one, even though I was trying to be careful. At the time of writing, nobody else in my household has received their results; or to put it another way, no results have been assigned to the identifying details of any other patients in the household except me.

Live-action biosecurity games: petrol station

Well, time to go home. It was then 17:10 and I had spent six hours and ten minutes on testing that day. I had also driven a good few miles and it was time to fill up with petrol. I used a tissue to handle the petrol pump. There was no Pay At Pump, I had to go into the shop. With six hours’ work to catch up on, I also had no time to cook and needed to get some ready meals.

A security guard gestured to me to follow the one-way system, marked with arrows on the floor. I hovered on the spot like a video-game character, because a mum with a mask, and two children with no masks, were in my path. The unmasked kidlets were hooting and jibbering for joy. They let me past and I darted out of range, trying to keep out of other people’s way as I trolley dashed. A woman with a valve mask yelled to her sidekick “OKAY NOW YOU HAVE TO GO THIS WAY”. I sprinted to outrun her exhalations. And of course I’d spent too much on petrol to pay contactless, so I did the hand-gel juggle again and made a break for it.

I finally got home at 18:15, wiped down my groceries and my shoes, boiled my mask, replenished my hand gel and tissues in my bag, put my passport away safely. This took me until 18:45. In all, I had spent seven hours and 45 minutes trying to complete a COVID test. The first two to three hours were because of human error performing a complex task, and no-one is to blame for that; it’s part of the process.

Serco

What’s harder to understand is how a process that had gone smoothly until then, could cascade into failure as soon as I ventured outside my door. I checked the address of the second testing centre, and the mystery was solved: Serco.

Serco, that was done, and seen to be done, for serious fraud against the Ministry of Justice. “‘Unless government is satisfied [that they’ve changed], Serco will face exclusion from all new and future work with the government,’ the MoJ said.” So Serco’s directors defrauded the government, were convicted, yet somehow the company is the government’s choice for the contract on testing and tracing. Despite the evident willingness and best efforts of each of the three Serco telephone operators I spoke to, I encountered a series of data quality failures and was sent to two testing centres in succession that had “moved on” by the time I arrived. I was rate-limited on reordering a home test kit, but the telephone operator worked around it by creating a sockpuppet with a new email address and the same identifying details (as well as a slight variation on my name). The government has come under legal scrutiny for its handling of PPE procurement during the pandemic. There may turn out to be a good explanation for the government’s outsourcing and procurement decisions, but the choice of Serco does not inspire confidence in the meantime.

Lest I underemphasize these points, I had no symptoms when I was asked to take the test; I am privileged enough to maintain a lifestyle that minimizes my risk of infection; and I have sufficient resources and a flexible enough schedule to be able to drive off for hours in the middle of the day at the cost only of some lost productivity and petrol money. Take away even one of the privileges that enabled me to be resilient in this absurd odyssey, and the consequences could have been more serious. Indeed, there is no limit to how serious the consequences could be.

I had a similarly hilarious experience earlier this month. Had obvious covid-19 symptoms, but since I don’t drive my only option was a test kit. Sent off for one from the NHS website, without much confidence since I don’t think people who live alone and are totally untrained are likely to be able to take reliable swabs of themselves… but no other options were given. In the event, this was all irrelevant, because what turned up the next day wasn’t a test kit. What turned up was an empty box labelled as a test kit, left outside my door in the rain.

So I went hunting for rumoured local test sites. 119 was less helpful for me than it was for you: they had no idea if there were any in my area or where they might be, so I was going on local rumour: the local council had no idea either, and nobody knew who was organizing these things so nobody could even tell me how to find out. I really didn’t want to do this: by this point I was sufficiently badly off that walking was becoming difficult, but there was no other option if I wanted a test at all. After two hours staggering around the streets (just what you want infectious people to do in the middle of a pandemic, almost as dangerous as requiring ill people to drive) and finding three places where mobile test sites had been the previous week and no longer were, I gave up and went home. Four days later my neighbours told me one mobile test site had turned up again, but by then my symptoms were on the wane so I was almost certainly no longer shedding viable viral RNA and a test seemed increasingly unlikely to work.

I suppose this helps improve the government’s covid-19 statistics, but there’s no way it’s helpful in actually keeping the pandemic down. Hours of stress and effort is probably not much help in recovery from disease, either.

My father-in-law went for a bike ride and accidentally went through a testing facility. He’s in Leicester, which has been in lockdown (he lives just outside the lockdown area), however he said they were just sitting there with nothing to do. Apparently they jumped on him as soon as they saw him and insisted he be tested, although he was perfectly well (as confirmed by the test results).

I was randomly selected for the statistical program. The kit arrived a couple of days after I filled in the online acceptance form. Before you do the test, you go online again to arrange a collection (I did this on a Saturday and got a Sunday collection). On the day of the collection, you do the test (not hard but very unpleasant, I found), then you pack up the stuff, put the box in the fridge, and wait for the carrier to turn up. He came mid-morning, in the middle of the two hour slot they’d texted me. One final online survey I was done. The result (-ve) came back by text and email in the middle of the week.

I could fault it, really, other than how physically unpleasant it was – the logistics were exemplary.

@ Helen,

Having had the fun of putting your DNA and fingerprints on the samples, how do you feel about this Statutory Instrument,

“The Coronavirus (Retention of Fingerprints and DNA Profiles in the Interests of National Security) (No. 2) Regulations 2020” No 973.

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2020/973/made?view=plain

It’s just one of the reasons I say no to testing as I object to being treated as though I’m a proto-suspect or worse.

I don’t understand your concern here. The SI that you linked to is very clear that it is extending the period of time for which DNA and fingerprint information, which has been collected under other existing legislation (terrorism etc), can be retained. Despite the name of the legislation, it is not authorising the collection or retention of fingerprint or DNA data from the coronavirus testing program.

Vicky,

The SI is not actually that clear as anyone who has read through it will indicate.

But the issue is a bit more complex than just that SI. Any time any physical evidence is collected for what ever reason it can and often will be obtained by authorities.

When such information build up it frequently gets put in databases for various reasons that are unrelated to police or similar work.

But they end up being abused,

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/covid-police-database-1.5745481

Indeed, @Vicky.

@Clive, I am not worried that the test kit will be used to collect my fingerprints (which will be mixed with the fingerprints of multiple people) and DNA from the swab test before it is destroyed as clinical waste. I think that’s an unrealistic concern, and not a reason to avoid being tested.